Published: 11/20/2024

Dr. Victoria “Vicky” Avanzato, a first-year internal medical resident at Stanford University participating in the global health track, has a deep-seated passion for emerging pathogens — especially viruses. “Viruses are so cool from a research perspective because they’re just so elegant,” she says. “While bacteria have large genomes with many genes, viruses can cause devastating illness and pandemics while encoding just six or seven genes.”

Dr. Avanzato pursued her passion for viruses during her graduate studies, recently earning her MD and PhD degrees from Emory University School of Medicine and the University of Oxford through the NIH Oxford-Cambridge Scholars Program. Her research sought to understand the mechanisms by which antibodies neutralize viruses, virus protein structure, and antibody responses to vaccine candidates. She’s particularly focused on Nipah virus, a highly deadly but less-known zoonotic disease that first emerged in Southeast Asia around 25 years ago. Also in the Stanford Translational Investigators Program, Dr. Avanzato plans to pursue an infectious disease fellowship and hopes to continue studying emerging viruses, antibody responses, and the development of low-cost diagnostics following her residency.

Dr. Avanzato discussed her passion for viruses, her interest in global health, and her Nipah virus research, which is helping to lay the groundwork for possible vaccines and therapies.

What sparked your fascination with emerging pathogens, particularly viruses?

As a child, I was, ironically, a very paranoid germaphobe. I forced my parents and others to wash their hands, and once expressed my gratitude for my immune system during a Thanksgiving art project in elementary school. Over time, this obsession with germs transformed into a deep curiosity about how viruses work. I find them so fascinating — they’re not really alive, they have so few genes, and yet they can hijack the whole human body and cause some of the world’s most fatal infections. This inspired me to pursue my undergraduate major in Immunology and Infectious Disease at Penn State, and later to conduct research focused on how viruses affect human health globally.

I became fascinated by how the interplay between human behavior and the environment, including climate change, travel, and interactions with wildlife, contributes to the emergence of infectious diseases into our society. This led me to Nipah virus during my PhD research.

What makes Nipah virus a priority global health concern, and why is so little known about it?

Nipah is a paramyxovirus that circulates in fruit bats in Southeast Asia. It first emerged in Malaysia, causing an outbreak in 1998-1999 that killed over 100 people. It now causes near-annual outbreaks in Bangladesh and India. These tend to be smaller, in house-holds or healthcare settings. The virus poses a severe public health threat, with mortality rates ranging from 70 to 100 percent in recent outbreaks. It transmits to humans through an animal intermediate, such as pigs, or directly from bats through contaminated fruit or date palm sap. Concerningly, we’re now seeing some limited human- to-human transmission. More extensive human-to-human transmission would pose a huge public health risk.

Because it emerged in recent decades and has mainly impacted only Southeast Asia so far, many doctors in the US may not even learn about Nipah virus in medical school. But the risk of severe disease with high fatality rates, combined with the potential for human-to-human transmission, and the current lack of approved vaccines and therapeutics, make Nipah a major global health threat and it is designated as a priority pathogen by the WHO.

Given Nipah’s threat, there’s a push to develop vaccines and therapeutics. Tell us about your contributions to this work.

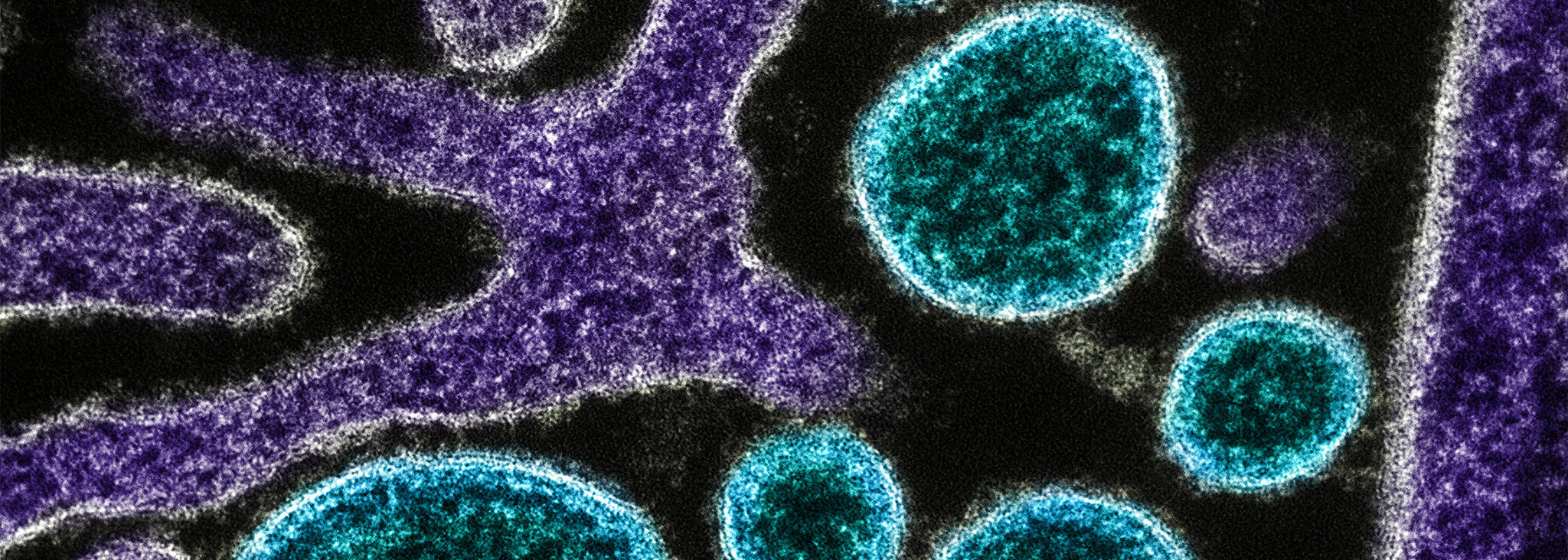

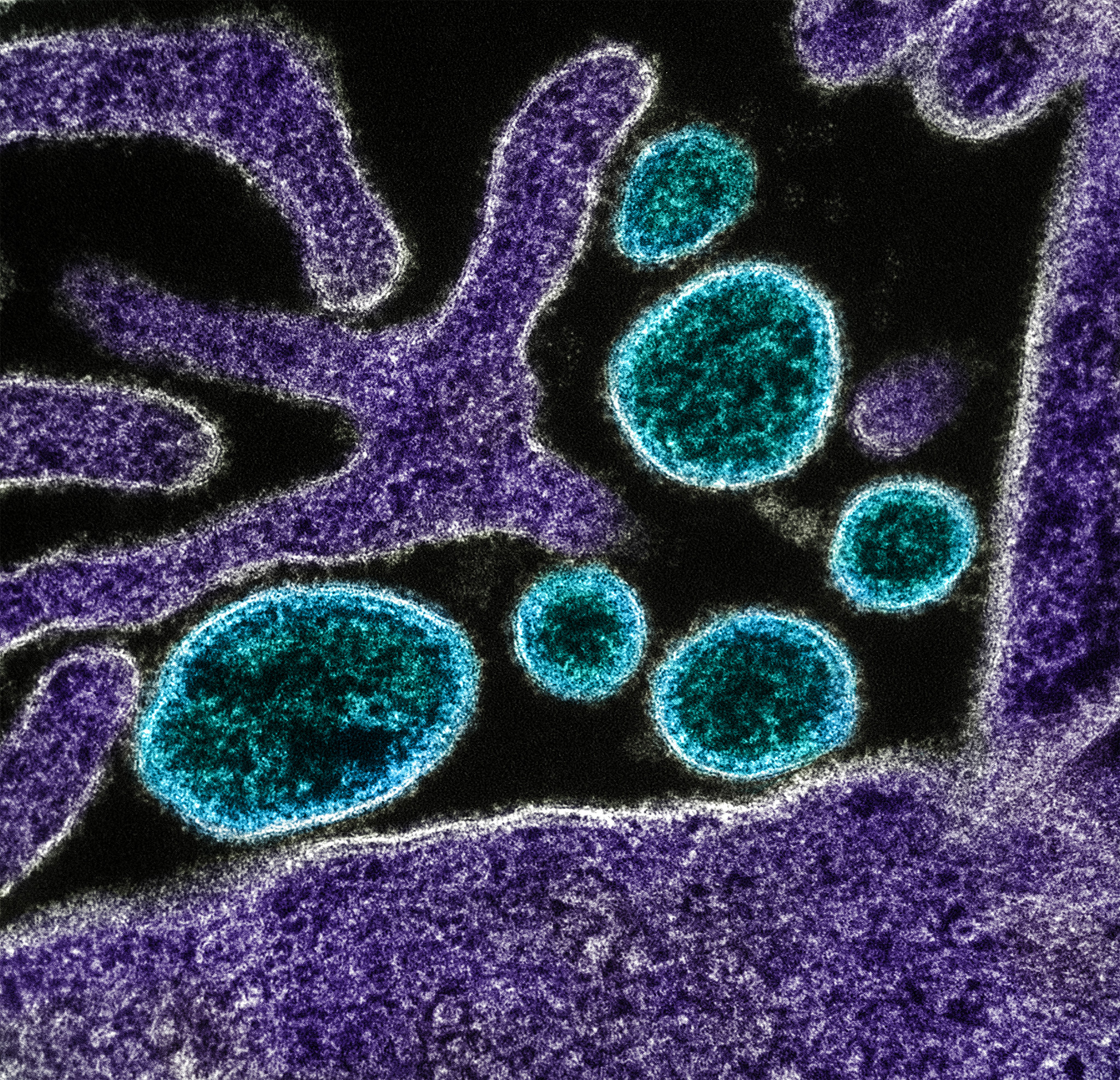

The main focus of my research was characterizing how monoclonal antibodies can neutralize Nipah virus. Specifically, I used X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy to determine where exactly these antibodies bind to the Nipah virus proteins. I focused on antibodies that bind the Nipah virus fusion protein, which allows the virus to fuse with and enter human cells. Antibodies binding to this protein can prevent the virus from infecting cells. My earlier work culminated in a 2019 publication that defined how a monoclonal antibody bound to a site on the Nipah fusion protein at the molecular level, identifying a site of vulnerability on the virus surface that could be targeted by antibody therapeutics or vaccines. My more recent work further explored this by utilizing cryo-electron microscopy to identify an additional antibody binding site in a similar region on the fusion protein. Then we tested this antibody in a hamster model and found that it completely protected them against infection from exposure to live Nipah virus. This is a promising indication that vaccines or monoclonal antibodies targeting the fusion protein could provide protection against this virus. There are currently no approved treatments or vaccines for Nipah, but there are several vaccine and antibody candidates in clinical trials currently, which is very exciting.

What attracted you to Stanford for your residency and post-graduate research?

Stanford impressed me with many opportunities for residents to engage in global health, and strong mentorship in the global health track. We have the opportunity to work with different patient populations during rotations abroad, but also domestically, including more underserved, vulnerable populations at the Fair Oaks Health Center, where I have my clinic. Working with diverse populations is an important aspect of my training in the global health track.

Additionally, Stanford Medicine’s Translational Investigators Program (TIP) will enhance my clinical training with invaluable research experiences. I’m particularly excited about combining my interests in basic virology and global health to study emerging infections. Multiple people are working on Nipah virus at Stanford, including an infectious disease fellow who did the global health track previously. After my interview, I thought, “These are my people! I have to come.”

What do you hope to learn and achieve related to global health and emerging diseases during your time here?

To this point, my work with Nipah has been very molecular — basic science focused on understanding the virus, antibodies, and protein interactions. During my residency and subsequent infectious disease fellowship, I’m excited to see how we can bridge basic science with broader global health applications — I want to see how we can apply the science to do good and empower our partner communities.

I really love my clinical training so far, but I’m also excited to dive back into lab work, especially focusing on antibody responses and low-cost diagnostic methods for emerging pathogens. Participation in global health initiatives, including elective programs where I can work directly with underserved communities, will be vital for me to form the collaborations needed to understand the real-world implications of my research.

Interview by Jamie Hansen, Global Health Communications Manager